The last couple posts on The Creator’s Roulette have been about finding reliable resources for a book and what makes good stories. Today’s post is yet another angle on writing a book that is well researched. Sharing her experiences on the series today, I have T. G. Campbell, an award winning crime fiction author who writes about a fictional group of amateur detectives called the Bow Street Society working in Victorian Era London. The group’s civilian members are enlisted for their skills and knowledge derived from their usual occupations.

T.G. Campbell has previously worked in the not-for-profit sector. First, for a project assisting offenders into training or employment, and then for a charity supporting victims and witnesses through the process of giving evidence at court. She’s also written articles for Listverse and Fresh Lifestyle Magazine. Her monthly blog includes interviews with a former police officer who worked at Bow Street and the curator of the Metropolitan Police Service’s historic collection. Let’s learn from her!

Writing a Well Researched Book

By T. G. Campbell

Before attempting to write a story set in a real-world period of history it’s important to answer one question; how faithful do I want my story to be to the reality of the period? The answer should also include the degree to which you’re prepared to include historical detail. For example, will you simply show the state of your character’s teeth, or will you describe their oral hygiene routine? Once you’ve decided upon the parameters of your commitment, you’ll have a clearer idea of the amount of research you’ve given yourself to do in preparation of writing your story.

Where should I start?

It’s a good idea to choose a specific window of time in order to narrow the scope of your research further. For stories which occur across a long period of time, I’d recommend focusing on no more than 10 years, unless you have intricate knowledge of the period’s historical context to begin with. Personally, I chose to set the first book in my Bow Street Society crime fiction series in 1896. This was because I wanted to explore the great period of change that was the late nineteenth century. It was a time when what we’d consider as “modern” was starting to emerge due to tremendous scientific and technological innovation. I also wanted to remove the possibility of my readers affiliating my books with Jack the Ripper by avoiding the infamous year of 1888. After choosing 1896 for the year, I settled on London, England, for the location. This was due to London being an internationally recognisable city that witnessed the birth of one of the oldest police forces in the world in 1829: the Metropolitan Police Service.

How should I organize my research?

The Bow Street Society is a group of amateur detectives who investigate cases posed to them by private clients. Each of the Society’s civilian members has another occupation in addition to being a detective and they use their skills and knowledge from these occupations to solve the crimes. Therefore, I have to ensure my portrayals of these occupations are as realistic as possible for the year of 1896. Thus, my research had to include the professional bodies/societies my characters would’ve belonged to and their history, the scientific knowledge my characters would’ve possessed, the technology my characters would’ve used, and my characters’ real-life contemporaries. For example, Society member and illusionist, Mr Percy Locke, can’t refer to illusions where he escapes as ‘escapology’ because the term wasn’t coined until the twentieth century. Additionally, his real-life contemporaries would’ve been Maskelyne & Cooke who regularly performed at the Egyptian Hall in London.

As the majority of my research centred on my characters’ occupations, I therefore organised it on this basis by creating folders for each character. I then carried out my research using this structure as my guide and stored the material I found within the folders. For example, Society member and hansom cab driver, Mr Samuel Snyder, has intricate knowledge of London’s transport networks and thoroughfares. I therefore stored material on omnibus routes and railway maps in his folder.

How do I know if my research is trustworthy?

This is often the biggest challenge encountered when conducting research. It may be overcome by scrutinising material in the following ways.

Is it a primary, secondary, and tertiary source?

Identifying which of these categories your research material falls into depends on who’s authored it and the context into which it was originally published.

- Primary Sources may be written accounts by eyewitnesses of an event, or a photograph/film of the event as it happened. Although these sources appear to be the most trustworthy on paper, it’s important to remember that eyewitness testimonies are notoriously subjective. They can therefore be inconsistent and inaccurate due to the influence of peers and/or an individual’s prejudices, ignorance, or misunderstanding.

- Secondary Sources may restate information from a primary source in order to analyse or review its contents, e.g. textbooks. I also put second-hand eyewitness accounts, histories, and academic critical analysis written long after the event into this category.

- Tertiary Sources have condensed other sources in order to index, abstract, organize, or compile them, e.g. almanacs. Some sources can be both secondary and tertiary, though, e.g. encyclopaedias.

The rule of threes:

Wherever possible, try to find three separate items of credible source material which corroborate one another. This should lower the risk of inadvertently passing on misinformation as comparing the material should highlight inconsistences and blatant untruths.

Where should I look?

You should be wary of certain websites which allow anyone to edit the articles. Even if you’re reasonably confident about the information in those articles, including such websites in your research will reduce your credibility.

Charity and second-hand bookshops are excellent sources of cheap, out-of-print books. Websites such as The National Newspaper Archive, the British Medical Journal, the National Archives’ online catalogue, and Lee Jackson’s Dictionary of Victorian London are also excellent resources for “of-the-period” material. When possible I like to visit temporary exhibitions, such as the Museum of London’s Crime Museum Uncovered exhibition, in addition to permanent museums like the Old Operating Theatre & Herb Garret. Whenever I’ve had a specific research question in mind, I’ve also contacted museum curators and archivists of professional bodies. For example, the Salter 5 typewriter used by Society clerk, Miss Rebecca Trent, was recommended to me by the curator of the Virtual Typewriter Museum.

How do I incorporate my research into my story?

When planning and writing a story based upon research it’s important to remember that your research should inform your story as much as your story informs your research. Usually, I’ll first create a plot plan for my next Bow Street Society mystery. Second, I’ll list the areas of additional research I need to conduct to ensure my plan is feasible, e.g. could my surgeon character detect a particular poison in 1896? Third, confirm and alter elements of my plan based upon the research material I’ve uncovered.

The degree to which this historical information is incorporated into my story depends on how much I committed to including at the start of the process. Ultimately, how you write your well-researched book depends on you.

What are some ways you keep track of research for your book?

Hope you enjoyed this post by T.G. Campbell. Learn more about her on her website and connect with her on Twitter and Facebook. All her published works can be found here.

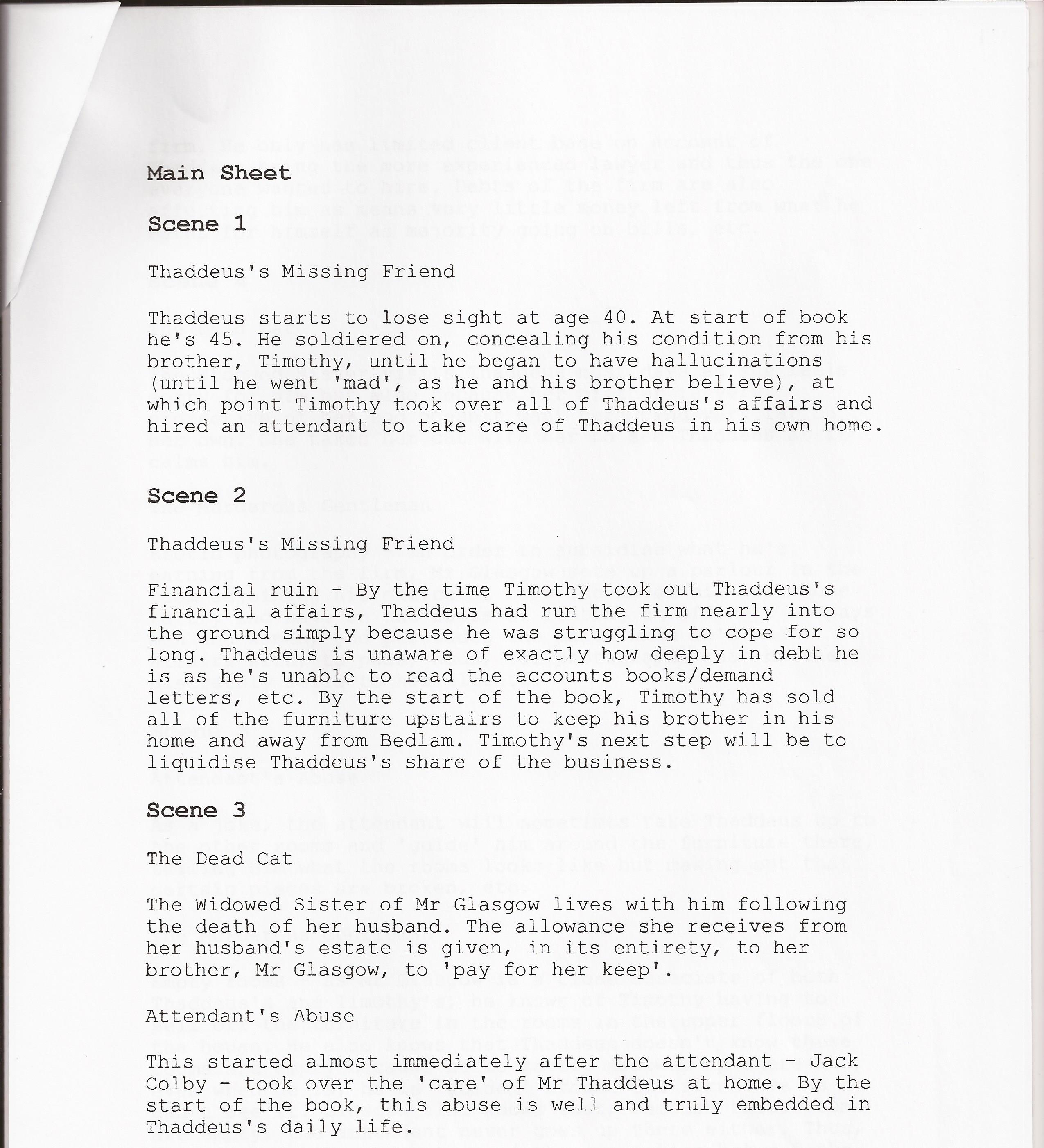

Banner image from Unsplash. Screenshots of the story plan, storylines and script by T. G. Campbell.

Thank you for the amazing opportunity to be a part of The Creator’s Roulette. I’m happy to answer any questions readers may have about either writing a well-researched book or my series in general.